Tackling Everest

‘That was my Everest’…

An oft-used metaphor signifying the toughest challenge ever encountered by the user. Writing a thesis, overcoming a phobia, making a fundamental life change, whatever it may entail, mention of the World’s highest mountain is synonymous with epic-scale struggle.

‘Because it’s there’…

The famous quote attributed to British mountaineer George Mallory, made to a New York Times journalist in 1923 to justify the reasons behind his seemingly impossible attempts on the mountain that took his life the following year.

Because It’s Everywhere

Of course, attempting to climb the mountain itself is the preserve of those experienced enough, or more recently affluent enough to pay for the guides, permits and equipment required to spend the requisite time high in the Himalayas. However, thanks to the imagination and inventiveness of the infamous ‘Hells 500’ crew, a verified attempt at Everest’s elevation has become open to anyone with a GPS watch and access to some hilly terrain.

Who are Hells 500?

Hells 500 are a collective of cyclists famed for eschewing traditional racing, instead focusing their masochistic tendencies on outlandish personal challenges, often taking place in the harshest of conditions. They are the self-titled ‘creators and custodians of the Everesting concept’ and are the organisation to whom Everest aspirants submit their data, anxiously waiting and hoping for admittance into the coveted Hall of Fame.

What is Everesting?

It truly is a beautifully simple but fiendishly difficult challenge. It can take place on any hill, anywhere in the world and can be tracked by any device that runs Strava. By selecting a valid segment and ‘simply’ repeating enough times to generate 8,848 metres of ascent and descent, the Everest is completed. Participants may stop and refuel, resting destroyed limbs for as long as required, but sleeping is strictly forbidden and the attempt must be undertaken in a single effort. For the vast majority of aspiring Everesters the immensity of the challenge in itself is enough, but there will always be athletes who strive to trim the fat from the ticking clock and post the fastest times possible. This is where my interest became piqued.

Contador Versus McLaughlin

Alberto Contador, multiple Grand Tour winner and one of the most successful professional cyclists in recent decades held the cycling Everest record. ‘El Pistolero’ needs no introduction and despite sharing the controversies that shadow so many of his generation, he is undoubtedly recognised as amongst the greats of the sport. Ronan McLaughlin is an extremely talented Irish cyclist, former professional and international competitor but self-admittedly no world-class GC contender. And yet it was the Irishman who obliterated the Spaniard’s Everest time to shock the cycling world and prove that when it comes to Everesting, with the right segment and enough talent, truly anything is possible.

As an acquaintance of Ronan’s, that performance really struck home to me, realising that somebody I know could topple the superstars. As the shockwaves reverberated through the Cycling press, a seed instantly blossomed in my mind and rapid research commenced, what was the world record for the running version?

It didn’t take much more than consulting the Everesting website and then a spot of Googling to discover that the up and down record (there is an uphill only version too) was held by Canadian Ryan Atkins, the world obstacle course race champion, with a phenomenal 11 hrs 19 minutes, set in early June on a ski piste in Sutton, Quebec. In terms of profile, Atkins is somewhat similar to Contador, a household name in extreme endurance sports with a physique, lifestyle and internet presence befitting of a man at the top of his game. Me, I’m probably best described in similar terms to Ronan, elite athletes and international standard competitors in our own rights but not quite from the upper-echelons. Amusingly we’re both professional coaches, ‘those who can do, those who can’t teach’! His performance fired me up no-end though, the plucky Irishman, David versus Goliath, the possibility of holding both the world’s best Everest times on this wee island got the competitive juices truly bubbling. Following a return from two years of injury hell with a record-smashing victory at the Irish world championship trials, confidence was high that peak form had finally returned to me. With that hurdle surmounted, thoughts turned instantly to how to tackle this next challenge, keen to ride the rediscovered wave of fitness.

Technophobes and Route Searches

The physical aspects provided little anxiety. The longest I’d ever run for previously was five and a half hours at the World Ultramarathon Champs a few years back, but the unknown nature of pushing hard for over eleven hours provided excitement and interest rather than apprehension. However, the technological facets of actually tracking and recording the attempt brought much greater barriers, and as a self-confessed technophobe I was much more concerned with not making a total mess of the GPS data; time to enlist some help. A call to Ronan was invaluable to allay my major worries, it truly is all managed through Strava with verification assisted by heart-rate data, power outputs, photos and any other evidence you can provide to prove the validity of your attempt. Then it was a quick lesson on segment creation from my friend Caoimhe, and we set about finding the straightest, steepest section available on which to most rapidly accrue the height.

Credit: Unknown

The Art of the Segment

Although an Everesting can take place literally anywhere with a traceable elevation change, tracking down a suitable spot for a fast attempt is more complicated. Steep gradients result in rapid gain and minimal overall distance to run, but obviously they’re much harder to negotiate at speed, particularly on the downhills that batter quads to death at much over 25%. Shallower slopes are eminently more runnable but will require far greater ground coverage to rack up the metres. Physiologically, as a pure mountain runner I’m much more attuned to the steeps as opposed to the epic distances familiar to trail specialists, and so the 34% average of Slieve Donard’s summit ridge looked a possibility. The exposed nature of Northern Ireland’s highest peak and the underfoot combinations of granite marbles and sodden turf are hardly built for speed but beggars can’t be choosers and it offers a consistently steep 250 metres of climbing.

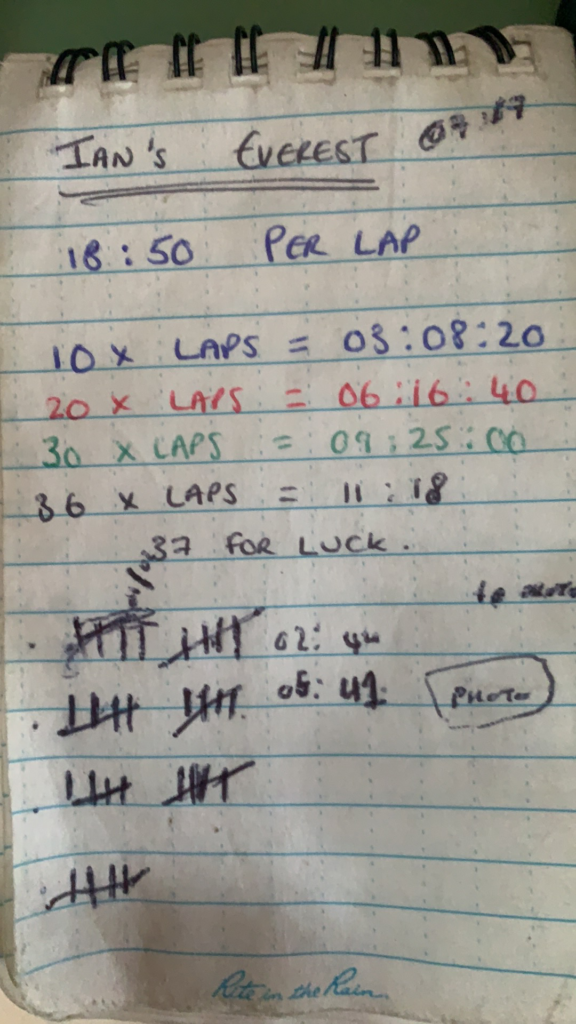

As a popular walking and running route, the chosen section was already well established on the Strava activity tracking app, and following a few tweaks to remove the curved end towards the col, ‘Everest 2’ was created. This was then fed into the Lap Calculator and the necessary stats were generated; my run would require 36 laps, for a total of 32 miles and an overall elevation gain of 8,964 metres, outlandish but certainly not impossible.

Testing 1,2,3… 10

Of course, the segment had to be tested, times tallied and feasibility analysed. I wasn’t about to start proclaiming a record attempt without at least ascertaining its possibility. So with legs a touch heavy from the previous week’s racing and a moderate but persistent headwind, ten laps were completed on a soggy Sunday morning. 3:01:29 felt comfortable, an average lap time of 18:09, just over forty seconds per lap faster than Atkins’ effort which took place on a hill with almost exactly the same elevation gain. With better conditions, a bit of rest and some proper sustenance it seemed just about possible that a suitably fast pace could be maintained for over eleven hours, but it was also abundantly clear that there could be no let up in pace or pauses for any reason. Time to start studying the weather forecast incessantly.

Storm Ellen

Summer in Ireland is a bit of an abstract concept. Generally it takes place over a couple of weeks in May, annually raising our hopes of months of sun-soaked glory before smashing them to pieces by September. This year has been the usual bizarre mix, three months of almost unbroken drought accompanying the peak of the Covid lockdown, followed by a succession of storm fronts, biblical rains and battering winds. The preceding week had been ideal, benign and dry with the unique experience of running a mountain marathon in Limerick and almost suffering heat stroke. Storm Ellen smashed through as a reminder of how fickle weather systems can be, especially on an island at the edge of the Atlantic. Hopes of an immediate attempt seemed extremely unlikely until a hint of a temporary reprieve the following Sunday. Latching on to that possibility, ‘preparations’ went into overdrive, in reality meaning a trip to Tesco for a ton of jelly babies and an unhealthy obsession with weather apps, switching rapidly between a selection of four, hanging on to the most optimistic and trying to ignore the least.

A Westerly breeze was a positive; the promise of constant precipitation, zero visibility, clammy humidity and heavy, soaking ground less so. Nevertheless, impatience was brewing and Sunday was gaining that inevitability that accompanies this sort of challenge, often flying in the face of reasoned sense. A stroll up to stash some bottles and peg out the optimum descent line became an epic struggle in 90kph winds and horizontal rain; amusing enough with hindsight and a hot cup of tea but not exactly encouraging for an already faltering confidence. Back to the apps once more. Ultimately, an eleventh hour chat resulted in a classic Irish ‘sure we’ll give it a lash’ decision and the attempt was on.

Lonely Strolling

So it was that I found myself trekking through the pre-dawn gloom of a murky morning, skirting around puddles, vaguely conscious of moving towards a certainty of pain. The psych was gently stirring but also the fear, and legs dragged slowly, a mix of energy preservation and a wilful delaying of the inevitable. Half way up, as the sun made a brief appearance on my back, a halo of light illuminating the hillside, it dawned on me that it’s quite a long way to the col. Normally a half-hour run, at walking pace it dragged frustratingly and minutes passed, plans for an early start disappearing. Cresting the steep steps to the flattening saddle, the familiarity of the summit ridge appeared through the mist, already a very close acquaintance from numerous training efforts but about to become the sole focus of an entire day. Caoimhe was already there, placing the turning-point flag, ready for a quick pep-talk and a fist-bump before the watch tracker beeped and with a gentle skip over the grassy hummocks the effort began.

Laps 1-10, Easy Street

Regardless of any degree of self-restraint, the first climb was always going to be a little too hot. Legs pumping and calves a touch tight as blood began to flow faster, muscles complaining at the rude awakening. The summit almost a surprise and a top fifty overall Strava time on a segment that has been used for international trials as well as one of Ireland’s most prestigious mountain races. Skipping down the rough and slippery gravel, the mental pressure of apprehension physically lifted and the joy of rapid progress in the mountains came to the fore. Beyond the fleeting satisfaction of records, race wins, or any other external reward, the true joy is the privilege of being able to flow where others trip and stumble, high amongst the majesty of the peaks. Turn at the bottom and repeat, body comfortable and brain unencumbered by daily anxieties, the cleansing purity of enjoyable exercise.

Laps steadied slightly but remained sprightly, the only real challenge being the forced consumption of unwanted sugars, building glycogen stores for later depletion. Jelly babies a chewy challenge, a balancing act of breathing and swallowing alternately, trickier than the effort of the run. The 2500m mark ticked over and tenth lap was completed at 2hrs 49, ten minutes clear of personal schedule and over eighteen ahead of the existing record, would there be repercussions for this overexcitedness?

Laps 11-20, Into the Unknown

I read a really informative article about Atkins’ attempt just prior to my own and he mentioned the darkest moment coming around the three-hour mark as his body began to creak and strain, but the pace had to maintain, despite the knowledge that there were many hours still to negotiate. Laps eleven and twelve passed uneventfully but by thirteen the enormity of the task was dawning and an unhealthy obsession with the watch brewed. A deliberate decision to ignore time-splits until lap twenty returned my mindset to the simplicity of the task, and even passing the half-way mark brought little temptation to check progress. The bleak revelations of lap fourteen lifted gradually, one foot in front of the other and a constant effort output kept the loops accruing; the block took exactly three hours, twenty done and nearly a half-hour up on the record, so far so good.

Laps 21-30, Losing the Wheels

Mallory had to continually fend off accusations of futility, as have many others who operate at the outer-limits of human endurance and ability. Justifying the seeming selfishness of dangerous pastimes to the average sedentary individual can be a virtual impossibility. Whilst there was no immediate risk from my exertions beyond the possibility of collapse, there was an inevitability of deep psychological impact. Personally, I find the soul searching nature of these challenges to be the strongest enticement, and as someone prone to the complexities of my own brain’s self-destructiveness I find strength in overcoming mental adversities. To experience the elation, you also have to explore the darkness.

Around lap twenty-one, my wife Anna and two boys arrived at the col. Shouts of ‘come on Daddy’ brought rising waves of emotion and all was good in the world. Unfortunately, the legs were on a different wavelength, still smooth and powerful on the climbs but robbed of fluidity on the jolting steps and freefall gradients of the way back down. Lap pace disintegrated and suddenly the reality of how distant the end was smacked me hard, and the first slimy creep of self-doubt began to poke at the edges of resolve.

Blood drained from a face wrinkled with immediate anxiety, nervous glances exchanged with Anna as I passed jerkily downwards as my family ascended to the summit. By lap twenty-four I admitted to Caoimhe that I wasn’t sure if I could do it. Her reply was inadmissible but I’ll file it under ‘tough love’, and that verbal kick up the arse forced me through another couple of loops, it wasn’t just me invested physically in these efforts. Into the final ten and checking times every two, the buffer shrinking with every cramp-threatening plunge.

Sean’s arrival couldn’t possibly have been better timed, loneliness immediately dissipated and a caffeine block turned the lights back on. Others joined, and their gentle conversation proved the perfect distraction, all doubts eradicated, focus returning to maximising speeds. But despite the re-found motivation, battered calves continued to stab, jolts of pre-cramp accompanying every inevitable twist and slip on the greasy steps. Finally the left one seized, the electric pulse of muscles in spasm, rapid rubbing and valuable seconds wasted, still seven more times down this hill, bodily management essential but all to the detriment of time. This was going to go right to the line.

Laps 30-36, The Power of the Mind

Any endurance athlete will tell you that longer efforts are forged in the mind. It’s largely true, although that neatly avoids the thousands of essential hours logged in the legs too, hundreds of sessions molding into one, over years of physical exertion. The inspirational ones, the disappointing ones, the ones that cause sleeplessness and the ones that justify it all. Mountains, forests, beaches, gyms, all arenas of bodily enhancement, but also building blocks of self-assuredness. As the muscles strengthen, the grey matter remembers, doubts overcome and steely resolve refined. The brain is our super-computer, firing messages to the body but also taking heed of responses. I’ll never quite understand how the command to lock a muscle after twenty-nine laps can be completely overridden on the thirty-sixth.

The final six laps had been long-anticipated, the finishing straight towards the joy of being static, if only for a few minutes. But the previous ten laps had changed the game entirely, 9:09:50 at the thirtieth and the crushing reality of over two hours still remaining. Completion was beyond doubt, I could crawl the rest and still make it, but I came for a record and as much as I could lie and pretend it didn’t matter, that’d be an injustice to my motivations. It’s strange, as I’ve aged, acceptance of failure has developed; I guess that might be some form of maturity? But pride never dissipates and there are few harsher self-critics than me. I’d stated in advance that this would be the one and only attempt, all or nothing, and as the mental calculations accompanied the rapid ascending footsteps, it became evident that the 11:19 would be narrowly missed.

5, 4, 3, 2.. a distant figure heralded the return of my sometime training partner Mackers, himself an inspirational sportsman in another field. He’d been there for some early laps and somehow returned for the last two, despite a brutal ultra in his legs from just seven days previously. We’ll not mention that he ate the food himself that he’d carried up for me, and instead focus on the psychological lift of that gesture. Head down and charging, 12:29 for the final climb, my fastest since lap eleven, glancing at the watch as the magic 8,848 flicked by with 11:11:29 on the timer.

Now is probably a good time to explain how final results are calculated. Whilst it had become clear that 11:19 would pass before the chequered flag fell, because my total ascent surpassed the required 8,848 metres, my time would be rolled back by the percentage I’d gone beyond that mark. My foggy brain was still capable of extrapolating that sub 11:25 should suffice, and so hitting the summit a final time at under 11:18 created that possibility. I’d just somehow need to overcome the crippling stiffness felt on the previous fifteen descents.

And then it just happened. The stride lengthened and the clunky, self-preserving heel strikes were replaced by the tippy-toed lightness of the seasoned mountain runner. Floating over the grassy tussocks, barely touching the ice-like sheen of greased-wet granite. On to the near 50% stretch, sliding and leaping, and a self-fulfilling mantra, ‘don’t cramp up, don’t cramp up’. Finger fumbling for the stop button as I darted past the marker, 11:22:58, drop to my knees and stare back up the visible scar generated by thirty-six repeats. The heather will recover and so will my body, but for now we both bore the marks of the last half a day.

The Immediate Aftermath

An alarmingly orange pee, my first since starting all those hours ago. Ronan warned me that an hour after completing his own record-breaking effort his body went into shock and locked down. Fortunately for him he was in the back of a van, but I was still 600m above safety with a lengthy hobble to endure and an ominous storm front approaching. Elation fought with desolation as the icy rain cut through us, never so thankful as now for the mountain experience that expended more thought into safe extraction than the Everest attempt itself. Dizzy spells and waves of semi-consciousness, hot Chai with honey, the vital tonic imbibed. On a good day this 2.5 miles of treacherous ground passes in a whoop-filled fifteen minute blur; this staggered hike took four times that. Finally the sanctity of the van, hot air blasting and a very careful drive home.

Anna was waiting. Litres of sugary tea, soup, toast, anything to stop the hyperventilation and shaking, hands forming claws, neck rigid with pain. Smiles, weary conversation and profuse thanks to Caoimhe, she’d been up there the whole time. Then the indescribable joy of a hot bath and cosy bed. Midnight snacks and fitful sleep, a new day dawned, bright and beautiful, would’ve been much better conditions than those endured but that matters little now.

And Finally…

I’d equate waiting for the official result to be like when our first child was nine days overdue. Deep down I knew the time would be adjusted to about 11:17 but there’s always the doubts. Again, I’d love to be magnanimous enough to say it didn’t really matter, that completion of the challenge was reward enough in itself, and to some extent it was, but putting in that effort and missing out by seconds would’ve been hard to take. Confirmation came at 11pm, Hells 500 being based in Australia, a solitary beer and a wee social-media post then off to bed, job done.

Two days on and back into training. The body actually felt less battered than after a three-hour race, the measured pace clearly less destructive on the joints and tendons, meaning just the muscles had to be replenished. The familiar post-effort mental slump on Monday and then back to my usual semblance of normality. Everest took a definite toll at the time but bouncing back has been surprisingly painless.

Thanks…

Everesting is a brilliant concept, undoubtedly unbelievably tough regardless of where, when and how it’s completed. I’d guess that taking twenty-four hours is actually far tougher than eleven, but either way there’ll be bleak moments, euphoric highs and ultimately a warm satisfaction. Big thanks to Hells 500 for creating this opportunity for all of us to suffer.

As much as the physical efforts are a solo endeavour, there’s always a team of people behind the athlete and so thanks need to be liberally shared. My wife Anna is endlessly supportive of my obsessions, accepting the lengthy absences, nervous tension and expensive eating abilities with eternal patience. My friend Caoimhe was involved throughout the planning and execution, creating the segment, marking the route and then standing on the summit til the end, giving me food and much-needed cheer. Sean, Mackers and the other runners who joined for a number of laps provided exactly the distraction I needed at the time, and finally my boys Rowan and Dylan who hiked up to see me, as well as several others who shook off their hangovers to get shouty on a mountain side. Huge love to you all.